Outside Boston’s Faneuil Hall, where American revolutionaries first began clamoring for independence in the 1770s, the water is nowhere in sight. Tourists click photos, office workers hurry across the cobblestone paths, and everyone is perfectly dry. As I look around, I try to imagine a different Boston—a Boston of the future, a city that has to fear the ocean.

Extreme flood risk is just one of many dramatic changes that will come with a warmer planet. The average summer temperature in Boston stands to increase by as much as 14 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100, bringing with it a sharp rise in the number of deadly hot spells. In the 1970s this city experienced only

one 100-degree day per year. By the 2070s, forecasts call for at least 24 such hellish days annually.

For reasons researchers are still trying to sort out, four degrees appears to be a tipping point beyond which the human risks increase dramatically. Added sea-level rise, shifts in precipitation, and jumps in local temperatures could lead to vast water and food shortages. Nearly 200 million people could be displaced, and many of our standard methods of adaptation to weather extremes—developing new crops, bolstering freshwater supplies in advance of heat waves, responding to disasters after the fact—could have little effect. “In moving from two to four degrees you really do see, in all our best estimates, a major increase in the level of action required,” says climate-adaptation expert Mark Stafford Smith, science director for Australia’s national science agency. “Suddenly, dramatic adaptation is going to be needed”...

Image: Veer

This afternoon, Sept. 30, Fermilab will shut down the Tevatron for the last time. This story honors the operators - the men and women who have kept the accelerators running 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

This afternoon, Sept. 30, Fermilab will shut down the Tevatron for the last time. This story honors the operators - the men and women who have kept the accelerators running 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

Physics Today News Picks A blog of hand-picked science news from the staff of Physics Today Home Print edition Advertising Buyers Guide Jobs Events calendar DOE reshapes R transportation funding News Picks home A detailed map of the Japanese tsunami By Physics Today on September 30, 2011 4:40 AM No Comments No TrackBacks Geophysical Research Letters The 9.0-magnitude earthquake off the northeast coast of Japan last March caused a massive tsunami that devastated whole communities and led to a release of radioactive material from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant . Nobuhito Mori of Kyoto University in Japan and colleagues have now surveyed and mapped the impact of the tsunami along a 2000-km stretch of the coast . In the map below , red bars show the height above sea level , and blue

Physics Today News Picks A blog of hand-picked science news from the staff of Physics Today Home Print edition Advertising Buyers Guide Jobs Events calendar DOE reshapes R transportation funding News Picks home A detailed map of the Japanese tsunami By Physics Today on September 30, 2011 4:40 AM No Comments No TrackBacks Geophysical Research Letters The 9.0-magnitude earthquake off the northeast coast of Japan last March caused a massive tsunami that devastated whole communities and led to a release of radioactive material from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant . Nobuhito Mori of Kyoto University in Japan and colleagues have now surveyed and mapped the impact of the tsunami along a 2000-km stretch of the coast . In the map below , red bars show the height above sea level , and blue A new technique amplifies spin waves electronically and does not rely on external microwave sources. Published Thu Sep 29, 2011

A new technique amplifies spin waves electronically and does not rely on external microwave sources. Published Thu Sep 29, 2011 Researchers show that intershell recombination processes involving three and four electrons sometimes dominate over those involving only two. Published Thu Sep 29, 2011

Researchers show that intershell recombination processes involving three and four electrons sometimes dominate over those involving only two. Published Thu Sep 29, 2011 Fermilab’s Antiproton Source has long produced the antimatter that makes Fermilab’s particle collisions possible. While the Antiproton Source will shut down along with the Tevatron on Sept. 30, there are plans for its future.

Fermilab’s Antiproton Source has long produced the antimatter that makes Fermilab’s particle collisions possible. While the Antiproton Source will shut down along with the Tevatron on Sept. 30, there are plans for its future. On the eve of the shutdown of Fermilab's Tevatron, collaborators from the CDF and DZero experiments are expressing their gratitude for all the hard work and dedication that made 26 years of capturing billions of proton and antiproton collisions possible. In these final hours of operations, both collaborations are making the pen mightier than the proton by writing notes of thanks and appreciation.

On the eve of the shutdown of Fermilab's Tevatron, collaborators from the CDF and DZero experiments are expressing their gratitude for all the hard work and dedication that made 26 years of capturing billions of proton and antiproton collisions possible. In these final hours of operations, both collaborations are making the pen mightier than the proton by writing notes of thanks and appreciation.  The TOTEM experiment at the LHC has just confirmed that, at high energy, protons behave as if they were becoming larger. In more technical terms, their total cross-section – a parameter linked to the proton-proton interaction probability – increases with energy. This phenomenon, expected from previous measurements performed at much lower energy, has now been [...]

The TOTEM experiment at the LHC has just confirmed that, at high energy, protons behave as if they were becoming larger. In more technical terms, their total cross-section – a parameter linked to the proton-proton interaction probability – increases with energy. This phenomenon, expected from previous measurements performed at much lower energy, has now been [...] L’expérience TOTEM du LHC vient de confirmer que, à de hautes énergies, les protons se comportent comme s’ils devenaient plus grands. En termes plus techniques, leur section efficace totale (paramètre lié à la probabilité d’interaction proton-proton) augmente avec l’énergie. Ce phénomène, que des mesures réalisées à des énergies beaucoup plus basses laissaient entrevoir, a été [...]

L’expérience TOTEM du LHC vient de confirmer que, à de hautes énergies, les protons se comportent comme s’ils devenaient plus grands. En termes plus techniques, leur section efficace totale (paramètre lié à la probabilité d’interaction proton-proton) augmente avec l’énergie. Ce phénomène, que des mesures réalisées à des énergies beaucoup plus basses laissaient entrevoir, a été [...] On Friday Sept. 23, students arrived at control rooms for the LHC and its detectors throughout the evening in groups of five to 10. For the second time, members of the four largest experiments at the LHC at CERN were participating in Researchers’ Night, a Europe-wide event in which members of the public from more than 320 cities spend an evening alongside scientists in action.

On Friday Sept. 23, students arrived at control rooms for the LHC and its detectors throughout the evening in groups of five to 10. For the second time, members of the four largest experiments at the LHC at CERN were participating in Researchers’ Night, a Europe-wide event in which members of the public from more than 320 cities spend an evening alongside scientists in action. So this Friday is the shutdown of Fermilab’s Proton/Anti-Proton Collider the Tevatron. After almost 30 years of service and numerous discoveries the collider has run her course and is scheduled to be turned off. Instead of this being a sad event Fermilab is going to let the old girl go out with a bang! A [...]

So this Friday is the shutdown of Fermilab’s Proton/Anti-Proton Collider the Tevatron. After almost 30 years of service and numerous discoveries the collider has run her course and is scheduled to be turned off. Instead of this being a sad event Fermilab is going to let the old girl go out with a bang! A [...] While at Bari Conference (see here), the news was spreading that OPERA Collaboration, a long baseline experiment using muon neutrino beams launched by CERN by CNGS Project, detected a possible Lorentz violating effect. Initially, it started as a rumor in the comment area at Jester’s blog (see here). Then, Tommaso Dorigo provided a full account [...]

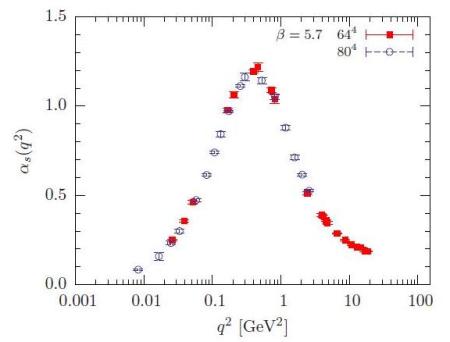

While at Bari Conference (see here), the news was spreading that OPERA Collaboration, a long baseline experiment using muon neutrino beams launched by CERN by CNGS Project, detected a possible Lorentz violating effect. Initially, it started as a rumor in the comment area at Jester’s blog (see here). Then, Tommaso Dorigo provided a full account [...] This week I was in Bari as the physics department of that university organized a major event: SM&FT 2011. This is a biennial conference having the aims to discuss recent achievements in fields as statistical mechanics and quantum field theory that have a lot of commonalities. The organizers are well-known physicists and so it was [...]

This week I was in Bari as the physics department of that university organized a major event: SM&FT 2011. This is a biennial conference having the aims to discuss recent achievements in fields as statistical mechanics and quantum field theory that have a lot of commonalities. The organizers are well-known physicists and so it was [...] A Fabry-Pérot cavity exhibits the same behavior when an atom replaces a mirror. Published Thu Sep 22, 2011

A Fabry-Pérot cavity exhibits the same behavior when an atom replaces a mirror. Published Thu Sep 22, 2011 : SUBSCRIBE TO NEW SCIENTIST Select a country United Kingdom USA Canada Australia New Zealand Russian Federation Other Log in Email Password Remember me Your login is case sensitive I have forgotten my password Register now Activate my subscription Institutional login Athens login close My New Scientist Home News In-Depth Articles Blogs Opinion TV Galleries Topic Guides Last Word Subscribe Dating new Look for Science Jobs SPACE TECH ENVIRONMENT HEALTH LIFE PHYSICS MATH SCIENCE IN SOCIETY The neutrino catcher that's rocking physics 17:39 23 September 2011 Physics Math Picture of the day David Shiga , reporter Read more : Neutrinos : Complete guide to the ghostly particle Image : Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nuclear Meet OPERA , a massive experiment shaking the world of physics that lies

: SUBSCRIBE TO NEW SCIENTIST Select a country United Kingdom USA Canada Australia New Zealand Russian Federation Other Log in Email Password Remember me Your login is case sensitive I have forgotten my password Register now Activate my subscription Institutional login Athens login close My New Scientist Home News In-Depth Articles Blogs Opinion TV Galleries Topic Guides Last Word Subscribe Dating new Look for Science Jobs SPACE TECH ENVIRONMENT HEALTH LIFE PHYSICS MATH SCIENCE IN SOCIETY The neutrino catcher that's rocking physics 17:39 23 September 2011 Physics Math Picture of the day David Shiga , reporter Read more : Neutrinos : Complete guide to the ghostly particle Image : Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nuclear Meet OPERA , a massive experiment shaking the world of physics that lies The OPERA neutrino experiment announced today the kind of result that keeps a physicist up at night. Scientists revealed that they have observed subatomic particles seeming to travel faster than the speed of light. Leaders of the collaboration will share OPERA data with the world today at 9 a.m. CDT during a seminar to be [...]

The OPERA neutrino experiment announced today the kind of result that keeps a physicist up at night. Scientists revealed that they have observed subatomic particles seeming to travel faster than the speed of light. Leaders of the collaboration will share OPERA data with the world today at 9 a.m. CDT during a seminar to be [...] Liquid helium-4 is integral in a source of slow-moving neutrons, with a five-fold increase in yield in density.<br/ Published Mon Sep 19, 2011

Liquid helium-4 is integral in a source of slow-moving neutrons, with a five-fold increase in yield in density.<br/ Published Mon Sep 19, 2011 Electric-field control of the spin-orbit field in [111] quantum wells lengthens the spin coherence time. Published Mon Sep 19, 2011

Electric-field control of the spin-orbit field in [111] quantum wells lengthens the spin coherence time. Published Mon Sep 19, 2011 Researchers propose using ultracold polar molecules to simulate the t-J model, the cornerstone of many theoretical efforts to understand high-temperature superconductivity. Published Thu Sep 15, 2011

Researchers propose using ultracold polar molecules to simulate the t-J model, the cornerstone of many theoretical efforts to understand high-temperature superconductivity. Published Thu Sep 15, 2011 Excited cold atoms in Rydberg states behave similarly to certain spin systems, providing us with a versatile toolbox with which to study nonequilibrium phenomena. Published Mon Sep 12, 2011

Excited cold atoms in Rydberg states behave similarly to certain spin systems, providing us with a versatile toolbox with which to study nonequilibrium phenomena. Published Mon Sep 12, 2011 Smallish black holes left behind from the early universe might cause detectible vibrations as they pass through the sun or other stars. Published Thu Sep 08, 2011

Smallish black holes left behind from the early universe might cause detectible vibrations as they pass through the sun or other stars. Published Thu Sep 08, 2011 Neng Xu, a software engineer for the University of Wisconsin-Madison working on the ATLAS experiment, sat drinking coffee in a sunny corner of CERN’s cafeteria when he thought of a challenge. Could he create a virtual version of what he saw out the window: a lawn with cafe tables and a building across the street?

Neng Xu, a software engineer for the University of Wisconsin-Madison working on the ATLAS experiment, sat drinking coffee in a sunny corner of CERN’s cafeteria when he thought of a challenge. Could he create a virtual version of what he saw out the window: a lawn with cafe tables and a building across the street? TweetTime holds a unique place in science and the human consciousness. Some say it is only an invention of the human mind that gives us a sense of order, a before and after so to speak while many physicists define it in terms of the physical properties of a space-time dimension. Both of these definitions [...]

TweetTime holds a unique place in science and the human consciousness. Some say it is only an invention of the human mind that gives us a sense of order, a before and after so to speak while many physicists define it in terms of the physical properties of a space-time dimension. Both of these definitions [...] It is some time I am not writing posts but the good reason is that I was in Leipzig to IRS 2011 Conference, a very interesting event in a beautiful city. It was inspiring to be in the city where Bach spent a great part of his life. Back to home, I checked as usual [...]

It is some time I am not writing posts but the good reason is that I was in Leipzig to IRS 2011 Conference, a very interesting event in a beautiful city. It was inspiring to be in the city where Bach spent a great part of his life. Back to home, I checked as usual [...] Forty-one percent of the children in Sudan are malnourished and underweight, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Mohamed Eisa, a physicist at the Sudan University of Science & Technology, would like to change this statistic, and he believes that particle accelerators can help.

Forty-one percent of the children in Sudan are malnourished and underweight, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Mohamed Eisa, a physicist at the Sudan University of Science & Technology, would like to change this statistic, and he believes that particle accelerators can help. The strand model, though my favorite, lacks a good explanation for particle masses. It does explain certain mass ratios, but it does not explain the absolute mass values. We should help on this topic.

The strand model, though my favorite, lacks a good explanation for particle masses. It does explain certain mass ratios, but it does not explain the absolute mass values. We should help on this topic. Magnetic ordering in a low-dimensional spin system cannot be generally excluded in the presence of spin-orbit interactions. Published Thu Sep 01, 2011

Magnetic ordering in a low-dimensional spin system cannot be generally excluded in the presence of spin-orbit interactions. Published Thu Sep 01, 2011 Scientists from dozens of countries and cultures mingle at CERN, home to the Large Hadron Collider. Last weekend, the laboratory announced plans to introduce a new element into the mix: artists.

Scientists from dozens of countries and cultures mingle at CERN, home to the Large Hadron Collider. Last weekend, the laboratory announced plans to introduce a new element into the mix: artists.  To complement normal NMR spectroscopy performed in high magnetic fields, researchers are developing a technique that works in nearly zero fields. Published Thu Sep 01, 2011

To complement normal NMR spectroscopy performed in high magnetic fields, researchers are developing a technique that works in nearly zero fields. Published Thu Sep 01, 2011 When searching for new physics at the Large Hadron Collider, researchers have to keep track of how many places they look. Published Mon Aug 29, 2011

When searching for new physics at the Large Hadron Collider, researchers have to keep track of how many places they look. Published Mon Aug 29, 2011